Working Conditions in Kidderminster Carpet Factories

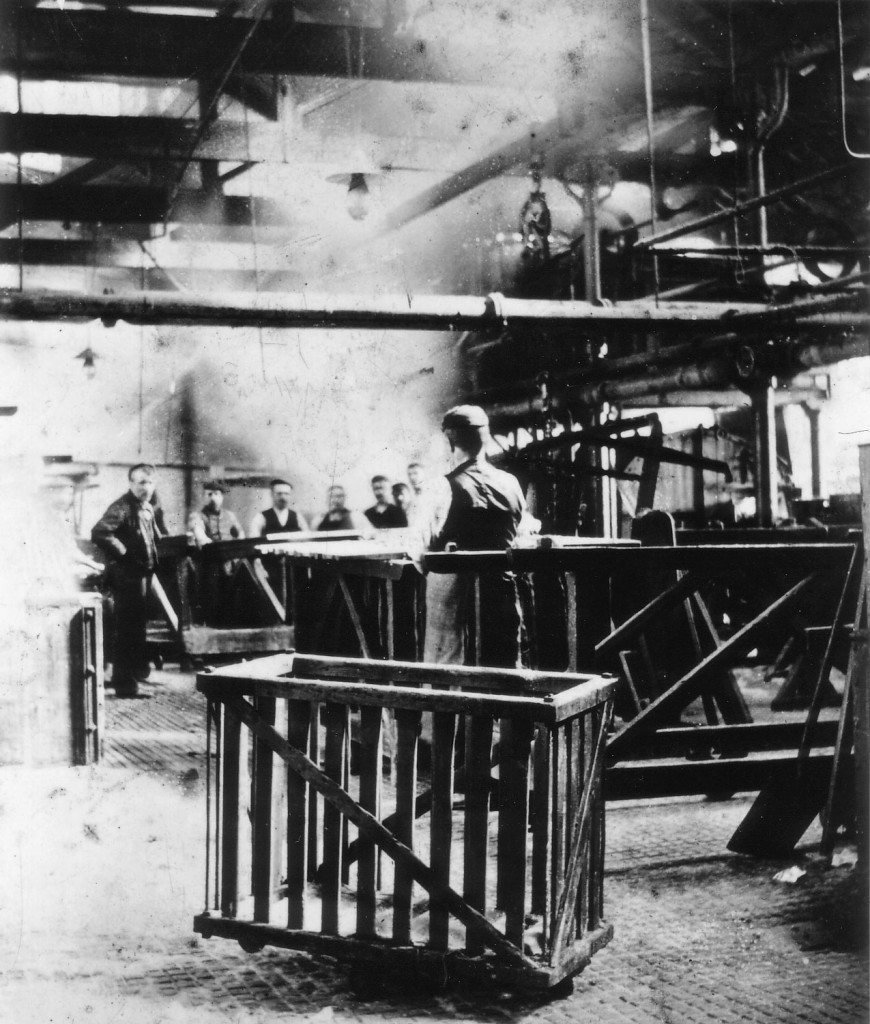

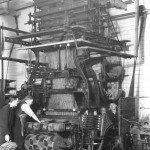

Image: Interior of a carpet factory. Though this photograph dates from the early 20th century, it provides some indication of the potential hazards which a factory worker could face in the 19th century.

Image from: Bewdley Museum

Conditions were hard for workers in the weaver’s home or in the larger carpet factories. The number of looms in any one place could vary between four, the most usual figure, to as many as sixty-six. The larger factories were usually arranged in multiples of four.

One witness at the Children’s Employment Commission in 1843 described the typical carpet factory as “large, regular, well-proportioned buildings of two or more stories, divided longitudinally into two, three or more departments by brick partitions, each containing four looms, two on either side” There was the ever present hazard of fire, even before the arrival of power driven looms, because of the close proximity of large piles of combustible yarns to candles, the only form of lighting. Privies were provided outside in the yards but workers were encouraged to use urine bins in the actual workplace, with no regard to the privacy of workers of either sex. Urine was a valuable commodity in the production of dye and the stench from the urine bins must have been appalling, especially when combined with the smell from the tubs of starch, which was used for coating the backing yarns.

A master weaver could work whatever hours he pleased as his working week was geared towards the Fall Days, Thursday and Saturday. After being paid on a Saturday, he often took the remainder of Saturday off. Sunday was naturally a rest day and Monday had traditionally been a rest day in the handloom period, known as St. Monday. This meant a long weekend, sometimes even extending into Tuesdays. Consequently, in order to complete his “piece” in time in order to be paid, a weaver was forced to work extremely long hours towards the end of the week. Joel Viney, a weaver, told the Factories Inquiry Commission just how long these hours could be. “I have known men to work from three o’clock in the morning till ten at night”

These practices prevailed even in the larger carpet factories, as the weavers had their own keys to the building and could work whatever hours they pleased, much against the wishes of the carpet factory owners. When special orders had to be filled quickly, hours could be even longer, with the use of twelve hour shifts worked back-to-back by two different shifts. These shifts were commonly known as “Twelve to twelve” and were extremely unpopular with workers.

Weaving was often a family affair. Wives and adult unmarried daughters were employed as bobbin winders and children were employed as draw-boys or girls, such was the demand for labour towards the end of the eighteenth century. Weavers often needed to have several looms in use, usually in blocks of four. They resorted to advertising for apprentices from elsewhere in Worcestershire, as shown by a letter to the Evesham Overseers of the Poor in 1808:

I take the liberty to inform you that I have been informed that you have several boys to put out as apprentices, if so, be pleased to let me know of what ages and sizes they may be and on what Terms, if there may be any from the age of ten years to fourteen.

Draw-boys served an apprenticeship before becoming a master or fully qualified weaver. For the last two or three years of an apprenticeship, if the lad was good enough, it was normal practice to pay him on half-wages as a half-weaver, using his own loom virtually unsupervised. In this way, the master weaver could get more work done. Apprentices were strictly supervised, in common with apprentices from other industries.

Girls never became full apprentices but were destined to become adult bobbin-winders or spinners, usually in the larger carpet factories. Their days as draw-girls were as long and arduous as that of the boys but they also had to contend with the amorous advances of fellow workers or their master weaver employer. One witness to the 1842 Factories Commission claimed that hundreds of draw-girls’ lives had been ruined by unwanted pregnancy over the last twenty years.

« Previous in this sectionNext in this section »Continue browsing this section

Made in Kidderminster: the History of the Carpet Industry

Made in Kidderminster: the History of the Carpet Industry

The Origins of Carpet Making in Kidderminster

The Origins of Carpet Making in Kidderminster

The Origins of Carpet Making in Kidderminster

The Origins of Carpet Making in Kidderminster

The Origins of Carpet Making in Kidderminster

The Origins of Carpet Making in Kidderminster

Handloom Weaving

Handloom Weaving

The Factory System

The Factory System

Washing and Winding

Washing and Winding

Washing and Winding

Washing and Winding

Technological Changes: the Scotch Loom

Technological Changes: the Scotch Loom

Technological Changes: the Brussels Loom

Technological Changes: the Brussels Loom

Technological Changes: the Jacquard Loom

Technological Changes: the Jacquard Loom

The Kidderminster Carpet Industry and the Wider World

The Kidderminster Carpet Industry and the Wider World

The Kidderminster Carpet Industry and the Wider World

The Kidderminster Carpet Industry and the Wider World

Working Conditions in Kidderminster Carpet Factories

Working Conditions in Kidderminster Carpet Factories

The Great Strike of 1828

The Great Strike of 1828

The Aftermath of the Great Strike of 1828

The Aftermath of the Great Strike of 1828

Kidderminster in the mid 19th Century

Kidderminster in the mid 19th Century

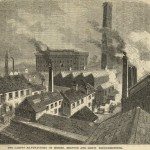

Kidderminster: the Factory Town

Kidderminster: the Factory Town