Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: Export Markets

Image: Merchant, The Book of Trades or Library of Useful Arts, Part II, third edition (London Tabart and Co, 1806). Merchants bought and sold goods and were an essential component of Birmingham’s industrial economy. The entries and advertisements in local directories show that the town had developed a large commercial community that engaged in the commercial aspect of the “toy trade.”

Image from: Science, Technology and Management, Birmingham Central Library

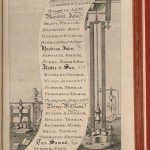

If the home market was important to the toymakers, the export trade was vital. In 1759, Samuel Garbett told a House of Commons Select Committee that there were at least 20,000 people employed in the ‘toy’ trade in Birmingham, producing goods worth some £600,000 a year, of which £500,000-worth was exported.1 This astonishingly high export trade was achieved by a small army of commercial travellers bumping and rattling across Europe in coaches, some employed directly by large manufacturers and some by Birmingham factors like Lewis & Capper, who represented several firms. Bigger manufacturers, like Boulton, also appointed local agents in some countries. The Birmingham makers faced tough competition from local manufacturers in some countries, notably France and Germany, but generally scored on price because they were more highly mechanized. Portugal and Sweden both imported a large amount of Birmingham goods until both placed prohibitions on Birmingham hardware imports to protect their own manufacturers. (“Hardware” in the 18th century covered the whole range of metal goods from fenders to jewellery.)

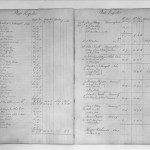

Boulton also investigated overseas markets himself, making visits to France and Holland. In his notebook for 1765, during a visit to Paris, he headed a list “We must make”. The list includes gilt, lacquered and plated buttons, steel snuffers, corkscrews, ear-rings, crosses, and a variety of buckles including “common steel” and “ditto fine”. His business partner John Fothergill spent months at a time abroad. In one letter, Boulton writes to a contact that Fothergill is to leave St Petersburg “by the first sledges that go to Narva, Metteau, Riga & Konigsburg”.2 In another, Fothergill writes of his desire to come home and the complaining letters from his wife about his long absence.3 In 1767 Boulton told a German business partner, J.H. Ebbinghaus of Iserlohn, “Steel Chains we have made immence quantity of this Year & have yet very great orders”.4 Three years later, a German firm offering to act as Boulton’s agents advised “We do not want samples of steel chains; the roads are paved with them in France, and there are no more sold.”5

1. House of Commons Journal, 20 March 1759.

2. MBP 307/46

3. MBP 307/53

4. MBP 135 Letterbook ‘C’, p.30

5. MBP 218/254

« Previous in this sectionNext in this section »Continue browsing this section

Birmingham: “The Toyshop of Europe”

Birmingham: “The Toyshop of Europe”

Toys in Birmingham

Toys in Birmingham

John Taylor and Matthew Boulton

John Taylor and Matthew Boulton

The Soho Manufactory: From Snow Hill to Handsworth

The Soho Manufactory: From Snow Hill to Handsworth

The Soho Manufactory: The Ingenious Mr Boulton

The Soho Manufactory: The Ingenious Mr Boulton

The Soho Manufactory: Industrial Tourism

The Soho Manufactory: Industrial Tourism

The Soho Insurance Society: Ahead of its time

The Soho Insurance Society: Ahead of its time

Birmingham Toys: Makers and Materials

Birmingham Toys: Makers and Materials

Birmingham Toys: The Hallmark

Birmingham Toys: The Hallmark

Birmingham Toys: Made at Soho

Birmingham Toys: Made at Soho

Birmingham Toys: “Cut Steel”

Birmingham Toys: “Cut Steel”

Birmingham Toys: Manufacturing Techniques

Birmingham Toys: Manufacturing Techniques

Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: The Home Market

Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: The Home Market

Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: Export Markets

Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: Export Markets

Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: Travelling Salesmen

Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: Travelling Salesmen

Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: Agents

Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: Agents

Summary and Developments

Summary and Developments