Introduction

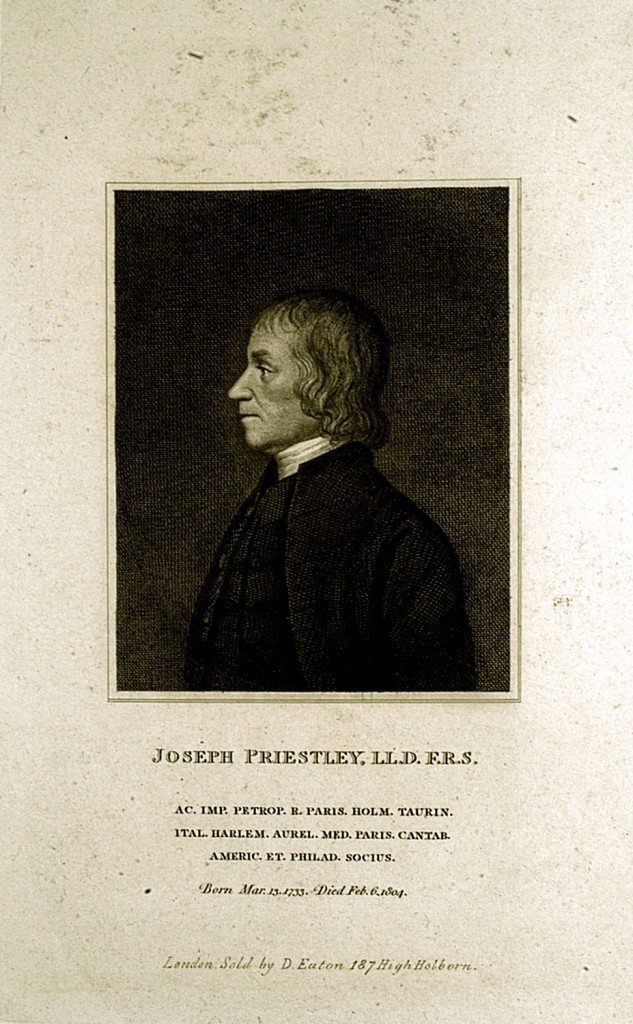

Image: Print of Joseph Priestley

Image from: Birmingham City Archives, Priestley Collection by Samuel Timmins

Two hundred years ago, on 6 February 1804, Joseph Priestley Doctor of Laws, minister of religion, theologian, scientist and political reformer, passed away. Thomas Cooper who was with him at the end wrote that same day to a mutual acquaintance: “Your old friend Dr Priestley died this morning without pain at 11 o’clock. He would have been 71 had he lived till the 24th of next month. He continued composed and cheerful to the end. He had been apprised of his approaching dissolution for some days.”1 Although he had been ill and in obvious decline since the previous November, Priestley had managed to keep on working in short bouts. And it was richly characteristic of the man that he should allow himself to die that morning only after having corrected some pamphlets which he had requested his son Joseph to bring to his bedside – religious pamphlets.

We mark Priestley’s passing by exploring the facets of a remarkably full and rewarding life. Yet it has to be acknowledged that he died a largely forgotten man. He died separated from his homeland in a remote and tiny settlement in the backwoods of Pennsylvania, America. He died separated from his scientific colleagues in Europe and almost completely out of touch with the experimental work in electrostatics and chemistry which he had done so much to advance in the early part of his career. He died, as he had lived, a religious outsider. And he died an unrepentant political exile whose enthusiasm for the actions of the French revolutionaries proved almost as distasteful to the Americans as it had to his fellow Englishmen.

At the religious service held to honour his memory at the Unitarian New Meeting Church in Birmingham in February 2004, the presiding minister described Priestley as a ‘man of candour’, a description that I would not dissent from – even if Priestley was capable of deceiving himself on occasions. He was a transparent man, a man who had no need of disguises, who never obfuscated, who was never slow to admit to a change of opinion. For a historian such as myself his life is relatively easy to follow, for much of it was spent in the public domain – under public scrutiny – and Priestley, as I have said, was not a man to wear masks.

It is true that the sources allowing us to reconstruct his life are now scattered; that the papers relating to the early and middle periods of his life were nearly all lost during the Birmingham riots of 1791; that Mrs Priestley had a tiresome habit of burning her own incoming correspondence; and that many of Priestley’s contemporaries either had their own correspondence destroyed in fires, or posthumously destroyed by overly solicitous relatives. Shortly before his death Priestley, too, disposed of some of his incoming correspondence, which is a shame. But much remains – not least the twenty-five volumes of his collected works. And as a social historian whose principal occupation up to now has been to coax inarticulate country dwellers to speak, I am more impressed by what we know, or can find out about Joseph Priestley, than by what remains inaccessible, or concealed from view.

My paper will provide an overview of Priestley’s career. The aim is to provide a frame of reference.

1 Birmingham Central Library, Archives of the Church of the Messiah 238, T. Cooper to J. Woodhouse, 6 February 1804.

« Previous in this sectionNext in this section »Continue browsing this section

The Life and Times of Dr Joseph Priestley

The Life and Times of Dr Joseph Priestley

Introduction

Introduction

Priestley’s Origins

Priestley’s Origins

Priestley’s Education

Priestley’s Education

Priestley’s Early Career

Priestley’s Early Career

Priestley and Lavoisier

Priestley and Lavoisier

Priestley and Nonconformist Leaders

Priestley and Nonconformist Leaders

Priestley and Birmingham

Priestley and Birmingham

Priestley and Birmingham

Priestley and Birmingham