Sir John Floyer and Lichfield

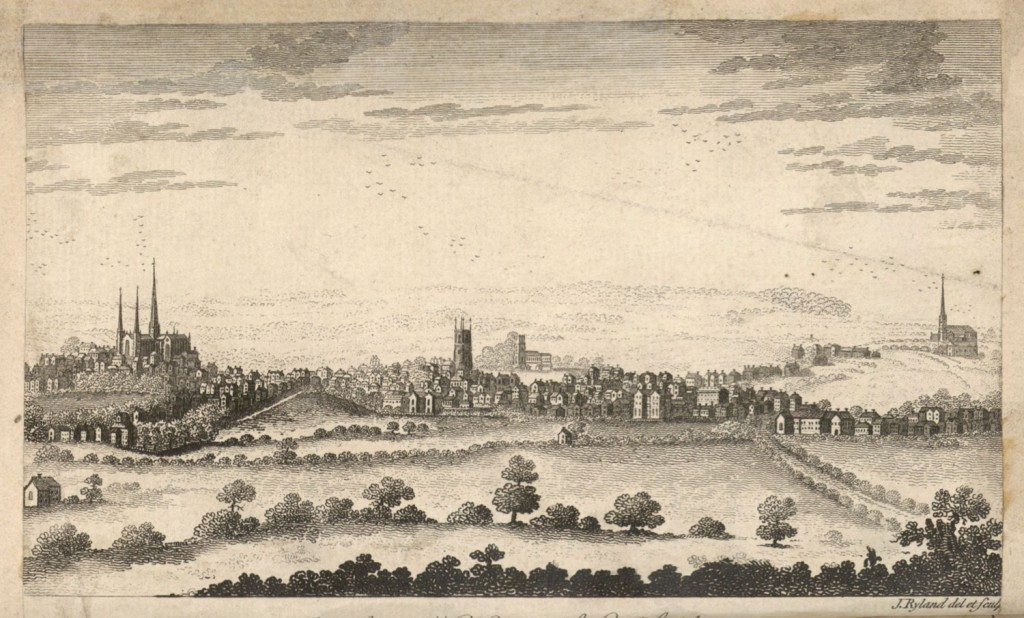

Image: South-west view of Lichfield, an eighteenth century print engraved by J Ryland and published in John Jackson, History of the City and Cathedral of Lichfield (London, 1805. Floyer probably lived in a house in the Close, near the West Front of the Cathedral which is depicted on the left of picture.

Image from: Local Studies and History, Birmingham Central Library.

Daniel Defoe described Lichfield in 1725 as a ‘place of good Conversation and good Company’. His opinion was probably based on meetings with the inhabitants of ‘a great many very well-built houses’ in the Close. Defoe must have met Sir John Floyer (1649-1734), who lived there. Floyer’s reputation and personality contributed to this flattering description of the town.

A native of Staffordshire, John Floyer was the third child of Elizabeth Babington and Richard Floyer of Hints Hall. At the age of 15 he started reading medicine at Queen’s College, Oxford. He graduated in 1668, and became a Doctor of Medicine in 1680. After Oxford he returned to Lichfield where he practised for more that half a century and here he wrote most of his medical and theological books.

John Floyer became an influential member of the community of Lichfield. He was knighted by Charles II in 1684, although the circumstances are not known. By marriage Floyer was related to Lord Dartmouth, one of the leading favourites at court. According to one of Dartmouth’s rivals, Floyer worked at Lichfield on Dartmouth’s behalf, ‘endeavouring to frame that corporation anew by leaving out some of the best men in it, that it may solely depend on that family.’ When in 1686 James II visited Lichfield, Sir John Floyer was a member of the party that met him on the outskirts of the city. In 1686 he was elected a Justice of the Peace; later he was elected bailiff. During 1690s, he served as a trustee of the city’s Conduit Lands; in the 1720s he regularly took part in the grand jury, and in 1729 became a trustee of the Lichfield turnpike trust.

Although knighted for his political services, Floyer also was obviously successful and respected as a physician, and his relatives even claimed that he had been physician to Charles II.

Floyer had a great respect for traditional Galenic medicine with its theory of the four humours or bodily fluids (blood, phlegm, choler and melancholy). Sickness is caused by imbalance of the humours, or by an insufficiency of one of them. To restore the patient’s health, doctors needed to bleed their patients, or to prescribe laxative or emetic medication. Herbal medicines were also used.

Floyer’s library which he donated to the Queen’s College, Oxford reflects the wide medical knowledge of a learned physician. It contained about 190 volumes. Most of them are medical treatises by German, Dutch and English physicians and scholars. He acquired many important works by Italian physicians of the Renaissance from his predecessor in Lichfield, Dr Anthony Hewett (c.1603-1684) who had read medicine at Padua.

Floyer’s lifespan coincided with the so-called Scientific Revolution. A contemporary of Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727), John Locke (1632-1704), Anton van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723), Gottfried Wilhelm Leibnitz (1646-1716), Floyer was conscious of the new experimental approach to science and medicine.

Floyer wrote a number of books on medical and theological matters which reflect contradictions in his points of view. He was sceptical about the use and utility of the microscope, and considered smallpox inoculation impious and sinful. He argued that the new natural science had added little to the achievements of Hippocrates and Galen. He constantly emphasised that he wanted to revive ancient practice, and not to innovate. In his later years he wrote an anti-Newtonian essay.

However, in some fields of medicine he was a pioneer. Floyer’s works reflect not only the strong influence of the great physicians of the past, but also his own inquisive mind, careful observation, and enthusiasm for experimental research. He often experimented on himself and criticised his fellow physicians ‘who caused their patients to swallow what they dared not taste themselves’.

« Previous in this sectionNext in this section »Continue browsing this section

Sir John Floyer (1649-1734), Physician of Lichfield

Sir John Floyer (1649-1734), Physician of Lichfield

Sir John Floyer and Lichfield

Sir John Floyer and Lichfield

Floyer’s Pioneering Medical Publications

Floyer’s Pioneering Medical Publications

Floyer and the Medical Importance of Bathing

Floyer and the Medical Importance of Bathing

Floyer and Samuel Johnson

Floyer and Samuel Johnson

Floyer and Erasmus Darwin

Floyer and Erasmus Darwin