Anti-slavery and the Midlands

- Introduction

The West Midlands region was home to a remarkable collection of individuals during the closing decades of the eighteenth century. Several men of various backgrounds and persuasions formed the Lunar Society, so called because it met at the time of the full-moon. They created new philosophies, scientific and medical approaches and industrial innovations which transformed the ways we understand the world, manipulate the environment and create wealth and labour. The Lunar men were also progressive politically and socially, but one area of their interest which has not been fully explored is their approach to slavery and anti-slavery.

The most extensive discussion of their approach to anti-slavery is contained in Jenny Uglow’s book, The Lunar Men. Biographies of Erasmus Darwin by Desmond King-Hele, Josiah Wedgwood by Robin Reilly and Thomas Day by Peter Rowland also draw attention to the commitments of these individuals. The Boulton and Watt Archives in Birmingham City Archives provide an insight into the ambiguous approaches of these two leading industrialists. The diverse responses of other Lunar figures, Joseph Priestley and Samuel Galton junior require exploration. The Lunar men had aspirations, some were motivated by humanitarian outrage or religious commitment. In other cases, profit outweighed or compromised principles.

- Slavery and anti-slavery

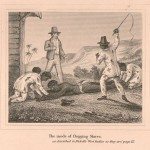

Slavery was central to the Britain’s Atlantic commercial empire in the 18th century. Black slaves from Africa were transported from Africa to the Caribbean and America to work on plantations producing sugar in the West Indies and cotton, rice and tobacco on the mainland. They supplied these products in increasing quantities to Britain. The slave system depended on two things: an adequate supply of labour and a buoyant market for the crops that slaves produced and processed. Britain was the most significant slave-trading nation by the late 18th century and the market for sugar sustained Atlantic slavery. British consumption of sugar increased ten-fold between 1700 and 1800 and the country consumed more sugar than the rest of Europe combined.

Most slave economies in the West Indies failed to reproduce themselves, so plantation owners argued that the slave trade was essential to enable demand for produce to be satisfied and maintain their profits. Ports such as Liverpool and Bristol depended on the trade for their prosperity and further inland Birmingham’s manufacturers profited from the guns that were exchanged for slaves and the shackles and chains that restrained them.

The anti-slavery movement had its origins in the efforts of individuals who were shocked by the cruelty of the slave trade and the inhuman treatment of slaves. They included Quakers and other Christians such as Granville Sharp, Thomas Clarkson, John Newton and William Wilberforce. In 1787 a committee was formed in London to demand an end to the trade. It formed the nucleus of a sophisticated campaign which attracted supporters from all social classes. By 1791 the campaign had secured the signatures of 400,000 people on more than 500 petitions against the trade. The Midlands was an important location for the attack on slavery and much of the credit for its depth and sophistication rests with individuals linked with the Lunar Society.

- • The local context

J. A. Langford in “A Century of Birmingham Life” (1868) traces the origins of anti-slavery in the town to a visit by Thomas Clarkson, the campaigner against slavery in 1787. Clarkson’s visit did seem to act as a catalyst and he singled out local Quakers as especially supportive, but this was not the only factor. In 1773, Thomas Day, who periodically resided in Lichfield and frequently visited his Lunar friends in Birmingham wrote “The Dying Negro”, a poem denouncing slavery which was a best-selling attack on slavery. The Unitarian philosopher, Dr Joseph Priestley was a leading abolitionist. In 1788 he delivered a sermon attacking slavery which was subsequently published. His attack coincided with a meeting in Birmingham to produce a petition calling for the abolition of slavery.

Other people added their weight to the local campaign. Aris’s Birmingham Gazette of June 28, 1790 notes that Matthew Boulton, Samuel Galton (presumably the elder) and Joseph Priestley, alongside other prominent local people, were subscribers to Olaudah Equiano’s, Interesting Narrative. This book was a best-selling attack on the slave trade and slavery which also provides a vivid account of his experiences as a West African who was forced into slavery and eventually achieved his freedom. Equiano is thought to have visited Birmingham in 1790 and later wrote thanking his supporters in Birmingham for their “Acts of Kindness and Hospitality”.

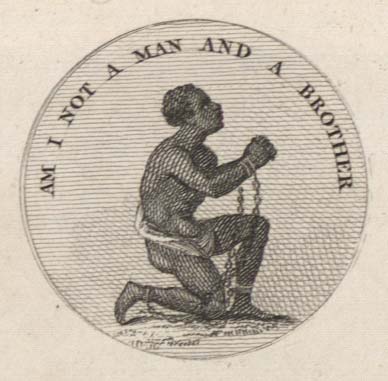

Other parts of the Midlands provided centres of activity. In 1787, the Unitarian Josiah Wedgwood produced his famous cameo which provided a public symbol for the abolitionist campaign and provided a nucleus for petitioning activity in Staffordshire. In Shropshire, where they were strong nonconformist and evangelical communities, Clarkson stayed at the home of Archdeacon Plymley and his sister Catherine who recorded local participation in anti-slavery activity in her diaries. John Wesley, the founder of Methodism and another convinced abolitionist visited the county frequently, staying at the Madeley home of the Rev. John Fletcher.

« Previous in this sectionNext in this section »Continue browsing this section

The Lunar Society and the Anti-slavery Debate

The Lunar Society and the Anti-slavery Debate

Anti-slavery and the Midlands

Anti-slavery and the Midlands

Anti-slavery: Poetry, Images and Ideas

Anti-slavery: Poetry, Images and Ideas

Commerce, Slavery and Anti-slavery

Commerce, Slavery and Anti-slavery

Abolition of the Slave Trade and Slavery

Abolition of the Slave Trade and Slavery