Impressions

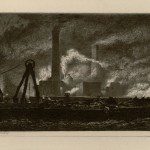

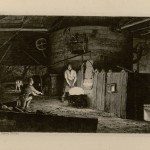

This image from the Illustrated London News (December 1866), illustrates the written impressions provided by a stream of 19th writers. The background presents a landscape packed with industrial activity and pollution from steam-powered chimneys. In the foreground relics of desolation and older activity remain, including a horse gin which had been used to draw coal out of a mine.

Few people went to the Black Country for its physical attractions in the late 18th or 19th centuries, unless they visited Dudley Castle or Shenstone’s Leasowes Estate near Halesowen. Visitors to the area, nevertheless, could not fail to notice the impact of industry. They included Charles Dickens (1840), Thomas Tancred (1843), Samuel Sidney (1851) and Elihu Burrit (1868). As early as 1785, Anna Seward (1742-1809) in her poem Colebrook Dale (1785) presented the industrial hinterland near Birmingham in verse. She may have had in mind the huge alkali works at Tipton, built by James Keir(1765-1820) in 1780:

So with intent transmutant, Chemists bruise

The shrinking leaves and flowers, whose streams saline,

Congealing swift on the recipient’s sides

Shoot into crystals.

In 1830 James Nasmyth walked to the Black Country from Coalbrookdale.

I proceeded at once to Dudley. The Black Country is anything but picturesque. The earth seems to have been turned inside out. Its entrails are strewn about; nearly the entire surface of the ground is covered with cinder heaps and mounds of scoriae. The coal which has been drawn from below ground is blazing on the surface. The district is crowded with iron furnaces, puddling furnaces, and coal-pit engine furnaces. By day and by night the country is glowing with fire, and the smoke of the ironworks hovers over it. There is a rumbling and clanking of iron forges and rolling mills. Workmen covered with smut, and with fierce white eyes, are seen moving about amongst the glowing iron and the dull thud of forge-hammers.

Amidst these flaming, smoky, clanging works, I beheld the remains of what had once been happy farmhouses, now ruined and deserted. The ground underneath them had sunk by the working out of the coal, and they were falling to pieces. They had in former times been surrounded by clumps of trees; but only the skeletons of them remained, dead, black, and leafless. The grass had been parched and killed by the vapours of sulphurous acid thrown out by the chimneys; and every herbaceous object was of a ghastly gray – the emblem of vegetable death in its saddest aspect….In some places I heard a sort of chirruping sound, as of some forlorn bird haunting the ruins of the old farmsteads. But no! the chirrup was a vile delusion. It proceeded from the shrill creaking of the coal-winding chains, which were placed in small tunnels beneath the hedgeless road.

After the coming of the railways, Queen Victoria closed the curtains of her railway carriage when she traversed the region’s landscape of furnaces, foundries and fire.

« Previous in this sectionNext in this section »Continue browsing this section

The Industrial Landscape of the Black Country

The Industrial Landscape of the Black Country

Geology

Geology

Industrial Origins

Industrial Origins

Impressions

Impressions

Illustrations of the Black Country Landscape

Illustrations of the Black Country Landscape

Blast Furnaces, Cradley

Blast Furnaces, Cradley

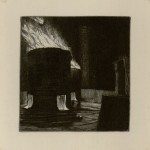

The Tunnel-Head

The Tunnel-Head

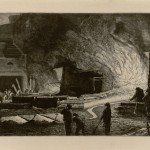

Tapping the Blast-Furnace

Tapping the Blast-Furnace

The Puddling-Furnace

The Puddling-Furnace